Application of a nano-antimicrobial film to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia: A pilot study

W. Li1, X. Ma1, Y. Peng1, J. Cao1, W. T. Y. Loo2,3,4*, L. Hao5, M. N. B. Cheung4, L. W. C. Chow4 and L. J. Jin3

1 ICU, Shenzhen People’s Hospital, Second Clinical Teaching Medical Centre, Medical College of Jinan University.

2School of Chinese Medicine, University of Hong Kong.

3 Faculty of Dentistry, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

4 UNIMED Medical Institute and Organisation for Oncology and Translational Research Hong Kong. 5State Key Laboratory for Oral Diseases and Department of Prosthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology,

Sichuan University, PR China.

Accepted 3 February, 2011

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is one of the most common hospital-associated infections and has accounted for approximately 15% of all hospital-associated infections. In 76% of the VAP cases, the same bacteria colonize the oral cavity and lungs. Oral care interventions may play a role in the prevention of VAP, yet more than half of the hospitals do not have specific policies for the oral care of intubated patients. Oral cavity interlinks with respiratory tracts and digestive tracts. After surgery has been performed in these areas, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria frequently induce operative wound infections in teeth, gingiva and supporting tissues of the teeth and tonsils. This study investigates the effects of a nanotechnology antimicrobial spray (JUC) on the incidence of VAP. 320 patients diagnosed with VAP were randomly divided into treatment and control groups. After using chlorhexidine mouthrinse, the treatment group used a nanotechnology antimicrobial spray to the nose and mouth. The control group was given normal saline. The incidence rate of VAP was significantly lower in the treatment (8.38%) than control group (54.24%) (p<0.01). A physical antimicrobial film is formed on the surface of oral and nasal mucosa after using the JUC spray which effectively reduces the microbial colonization in the sprayed areas, thus reducing and delaying the incidence of VAP.

Key words: Ventilator-associated pneumonia, oral care, nanotechnology antimicrobial spray, bacterial colonization.

INTRODUCTION

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is one of the most common hospital-associated infections and has accoun- ted for approximately 15% of all hospital-associated infections. It has been the second most common hospital- associated infection following its occurrence in the urinary tract, for which the mortality ranges from 1 to 4%. The

*Corresponding author: E-mail: tyloo@hku.hk. Tel: 852-9074- 9468. Fax: 852-2861-1386.

Abbreviations: VAP, Ventilator-associated pneumonia; WBC, white blood cell; CFU, colony formation unit; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CPIS, clinical pulmonary infection score; ICU, intensive care unit.

mortality rate for VAP which is defined as pneumonia occurring more than 48 h after endotracheal intubation and initiation of mechanical ventilation, ranges from 24 to 50% and can reach 76% in some specific settings or when lung infection is caused by high-risk pathogens (U.S. Department Of Health And Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control, 1997; Haley et al., 1981; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000; National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System , 1999; Bell et al., 1983; Celis et al., 1988; Chastre et al., 1998; Chevret et al., 1993; Craven et al., 1986; Craven and Steger, 1996; Cross and Roup, 1981; Delclaux et al., 1997; Fagon et al., 1989; Haley et al., 1981; Langer et al., 1989; Markowicz et al., 2000; Rello et al., 1993; Rello et al., 1997; Torres et al., 1990; Vincent

Li et al. 1927

et al., 1995). VAP is the most common infectious complication among patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and accounts for up to 47% of all infections among ICU patients (Charitos et al., 2009; Leroy et al., 2001). ICU patients are at high risk of infection with Staphylococcus aureus, whereas Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae usually dominate in postsurgical trauma patients. VAP prolongs ICU’s stay and increases treatment costs as well as the risk of death in critically ill patients (Carolyn et al., 2007; Chevret et al., 1993; Vincent et al., 1995). In 76% of the VAP cases, the same bacteria colonize the oral cavity and lungs (Chastre and Fagon, 2002; Doré et al., 1996). Oral care interven- tions may play a role in the prevention of VAP, yet more than half of the hospitals do not have specific policies for the oral care of intubated patients (Carolyn et al., 2007; Doré et al., 1996; Marra et al., 2009). Oral cavity inter- links with respiratory tracts and digestive tracts. After surgery has been performed in these areas, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria frequently induce operative wound infections in teeth, gingiva and supporting tissues of the teeth, tonsils, etc. (Salam et al., 2001; Senpuku et al., 2002; 2006). These infected areas generally offer bene- ficial environment, i.e. suitable temperature and humidity for bacterial proliferation leading to frequent infections.

In general, infections are commonly found in oral cancer patients after surgical excision of the tumor (Senpuku et al., 2003; Senpuku et al., 2006; Tada and Tanzawa, 2002; Tada et al., 2002; Zeng et al., 2008). This could be due to exposure of wounds during and after the operation. Patients, who received oral surgery often appear to have complications relating to bacterial infec- tions. Colonization of pathogenic bacteria in oral cavity is thought to increase the risk of infections such as pneumonia and bacteremia (Costerton and Greenberg, 1999; Gosney et al., 1999). Therefore, it is of high impor- tance to prevent bacteria from entering the lungs orally or nasally.

Currently, the systemic applications of antibacterial drugs have shown better results in curing diseases than local application, which may induce drug-resistant bac- teria in the particular area (Belusic-Gobic et al., 2007; Cloke et al., 2004). A nanotechnology antimicrobial spray, JUC, physical antimicrobial dressing was applied to some affected areas of oral cancer patients after surgery and proved to be a new physical antimicrobial method that does not have the tendency to lead to drug resistance (Zeng et al., 2008).

In this study, JUC spray was applied to the oral and nasal cavities of intubated patients in ICU to compare the incidence of VAP with conventional oral care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Actions and the quality control of JUC

The antimicrobial effect and quality of JUC spray were monitored and controlled by NMS Technologies Company ( Nanjing, China).

W hen water-soluble liquid of JUC was sprayed on skin surfaces or mucosal areas, it immediately solidifies and forms an invisible anti- microbial layer with dual overlapping structure; the bonded film and the positive charge film. The bonded film is composed of macro- molecular agents, securely boned to the body surface by means of chemical bonds. This bonded film has a long acting effect to prevent microbial growth. The positive charge film is composed of cationic activators to form a reticulate film with positive charge of the skin surface or mucosal area. The positive film strongly absorbs the pathogenic microorganism with a negative charge, such as bac- teria, fungi, and viruses. If the pathogenic microorganisms’ respiratory enzyme on which they rely for existence is out of action, they will die due to a lack of oxygen supply (Zeng et al., 2008).

This spray had been tested by Food & Drug Analytical Services Limited (Approval no: 9083481, USA) against Acinetobacter baumanii on a range of surfaces. JUC had passed all the tests on floor, metal handle, perspex, plastic handle and steel surfaces. Also, JUC had been tested by the University of New Brunswick (CE approval No: 153038905) on the zeta potential and hydrodynamic size of the dress sample. JUC demonstrated high zeta-potential values over a broad range of pH and the hydrodynamic size of the sample was 2.57nm in 0.5% aqueous solution.

Selection of subjects

From January 2009 to March 2010, 320 ICU patients requiring mec- hanical ventilation were recruited from Shenzhen People’s Hospital. Each patient was numbered and those of odd numbers were assigned to the treatment group ( 167 cases) and even- numbered were the control group ( 153 cases). Patients satisfying the following conditions were excluded: Under 18 years of age, history of using mechanical ventilation, pregnancy or lactating, pneumonia, bron- chiectasis, hemoptysis, pulmonary cyst or pulmonary fibrosis (Munro et al., 2009). Both treatment and control groups had teeth, oral mucosa, tongue and palate cleansed by chlorohexidine mouth- rinse every 8 h, 3 times daily for 5 days. Suction of 0.2 bar was used to withdraw mouthrinse from patients’ mouth. The treatment group was sprayed with JUC spray orally and nasally after mouthrinse. The studied protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen People’s Hospital.

Sample Collection

Tracheal secretion together with oral, nasal and throat swabs of the patients were collected every 4 h for 5 days for bacterial culture and identification after 24 h of intubation. Deep sputum samples were collected by protected specimen brush under bronchoscopy.

Criteria for diagnosis of VAP

The diagnosis of VAP must include persistent radiographic infiltration over 48 h, temperature over 38.5°C, total white blood cell (WBC) count 之10× 109/L and colony formation unit (CFU) test results over 103cfu/ml on protected specimen brush or broncho- alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid over 104cfu/ml ( Elie et al., 2006). According to the onset time, there are two clinical types of VAP, the early and late-onset VAP. The early-onset VAP is pneumonia that occurred within 48-96 h after intubation and mechanical ventilation while the late-onset VAP occurred more than 96 h after mechanical ventilation (Qinhua and Lixian, 2004).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 11.0 software package was used to collect and analyze

1928 Afr. J. Biotechnol.

Table 1. General information of 320 patients (![]() ±s).

±s).

Parameter | Treatment group (n=167) | Control group (n=153) | t value | p value |

Age(years) | 57.4 ± 15.2 | 55. 1 ± 14.8 | 1.371 | >0.05 |

Observation days | 8 41 ±2 10 | 8 27 ±2 07 | 0 596 | >0 05 |

APACHE ii score. | 21.62 ±6.78 | 22.47 ±6.27 | 1. 164 | >0.05 |

CPIS scores | 3.85 ± 1.58 | 4.03 ± 1.62 | 1.006 | >0.05 |

Table 2. Incidence of early-onset VAP patients.

Group | Number of cases | Incidence VAP (%) | X2 p value | Early-onset VAP (%) | X2 p value |

Control | 153 | 83 (54.24) | 79.51 | 42 (50.60) | 46.41 |

Treatment | 167 | 14 (8.38) | p<0.01 | 2 ( 14.29) | p<0.01 |

Table 3. Pathogens found in pharynx oralis (strains).

Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | Total strains |

Control | 63 | 50 | 38 | 36 | 30 | 22 | 18 | 20 | 277* | 22 | 25 | 324** |

Treatment | 8 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 32* | 2 | 3 | 37** |

A, Klebsiella pneumonia; B, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; C, Acinetobacter; D, Pseudomonas maltophilia; E , Escherichia coli; F, Enterobacter cloacae; G, Streptococcus pneumonia; H , Staphylococcus aureus; I, total number of VAP caused bacteria; J, Candida tropicalis; K, Candida albicans. *Significant difference between both groups at P<0 .01; **significant difference between the treatment group and the control group at P<0 .01.

the clinical data expressed as ![]() ±SD. The Q-test in analysis of variance was used to compare data between two groups. The t test in paired design was used to compare data collected at different time points within the groups. The rank test was used to compare the rate and constituent ratio of VAP.

±SD. The Q-test in analysis of variance was used to compare data between two groups. The t test in paired design was used to compare data collected at different time points within the groups. The rank test was used to compare the rate and constituent ratio of VAP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General information of patients

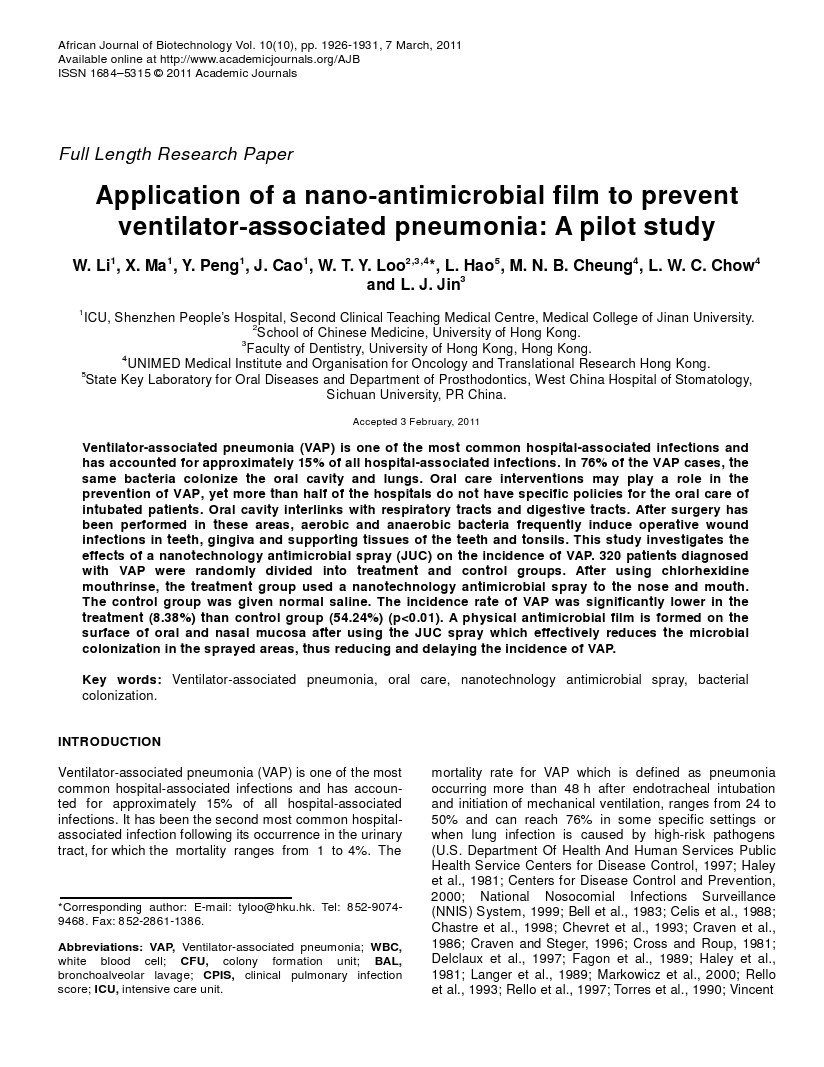

There were no significant differences in age, gender, rea- sons for ICU admission, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II, clinical pulmonary infec- tion score (CPIS) or days of admission to ICU between both groups prior to recruitment for this study (Table I).

Incidence of VAP

VAP occurred in 14 patients (8.38%) of the treatment group and 83 patients (54.24%) of the control group. Statistically, significant difference (p<0.01) was observed between the two groups (Table 2). Early-onset VAP was observed in 2 patients (14.29%) of the treatment group and 42 patients (50.60%) of the control group with signifi- cant difference (p<0.01) (Table 2).

Bacterial culture

10 types of pathogens were collected from 320 patients.

324 strains were isolated in the control group and 37 strains in the treatment group. The isolated strains were mainly composed of Gram negative bacteria including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter. There were significant difference (p<0.01) between the two groups (Table 3).

Deep sputum culture

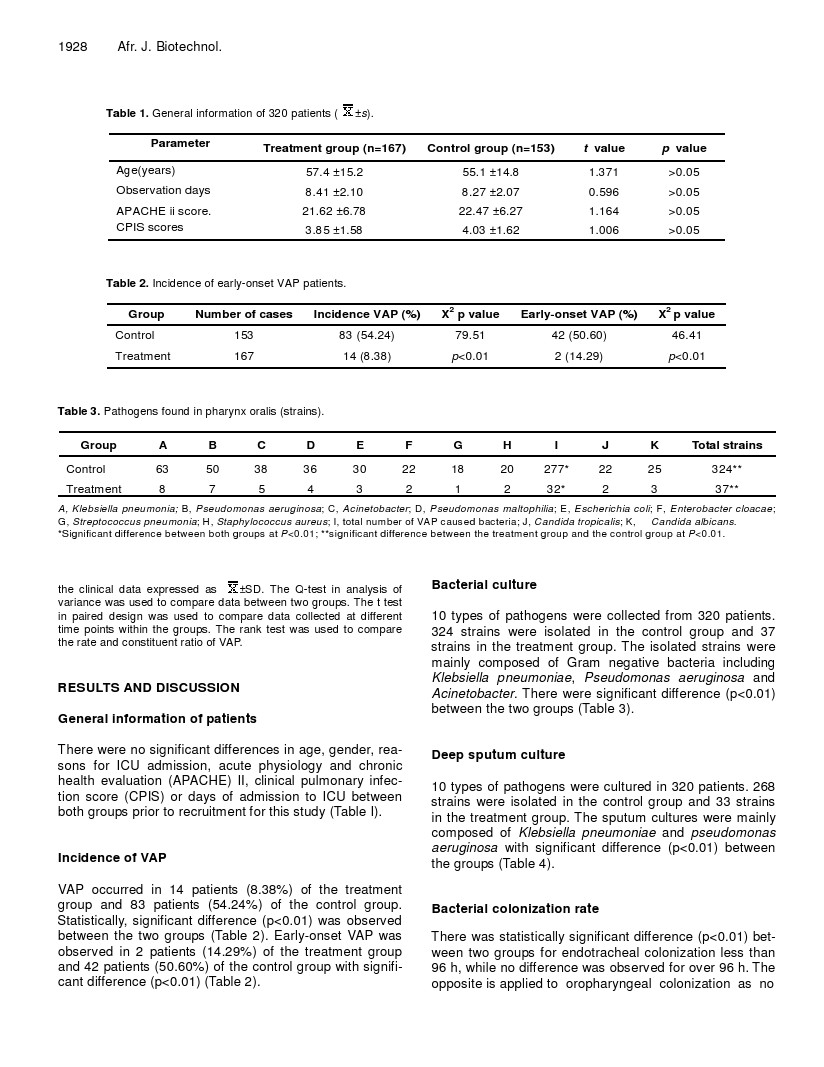

10 types of pathogens were cultured in 320 patients. 268 strains were isolated in the control group and 33 strains in the treatment group. The sputum cultures were mainly composed of Klebsiella pneumoniae and pseudomonas aeruginosa with significant difference (p<0.01) between the groups (Table 4).

Bacterial colonization rate

There was statistically significant difference (p<0.01) bet- ween two groups for endotracheal colonization less than 96 h, while no difference was observed for over 96 h. The opposite is applied to oropharyngeal colonization as no

Li et al. 1929

Table 4. Pathogens found in deep phlegm (strains).

Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | Total strains |

Control Treatment | 56 8 | 56 7 | 30 3 | 30 3 | 26 4 | 26 4 | 7 2 | 13 0 | 244* 31* | 14 2 | 10 0 | 268** 33** |

A, Klebsiella pneumonia; B, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; C, Acinetobacter; D, Pseudomonas maltophilia; E, Escherichia coli; F , Enterobacter cloacae; G , Streptococcus pneumonia; H, Staphylococcus aureus; I , total number of VAP caused bacteria; J, Candida tropicalis; K , Candida albicans.

*Significant difference between both groups at P<0 .01; **significant difference between the treatment group and the control group at P<0 .01.

Table 5. The rate of bacterial colonization in trachea and pharynx oralis between the two groups.

Region | Time of colony formation (h) | Treatment group (n=167) Control group (n=153) | 2 X | P value | |||

No. of cases | Bacterial colonization (%) | NO. of cases | Bacterial colonization (%) | ||||

Endotracheal | <96h | 4 | 2.40 | 5 | 3.27 | 0.22 | P>0.05 |

Mouth | >96h | 7 | 4. 19 | 34 | 22.22 | 23.24 | P<0.01 |

Nose | <96h | 5 | 2.99 | 7 | 4.58 | 0.55 | P>0.05 |

Pharyngeal cavity | >96h | 8 | 4.79 | 50 | 32.68 | 41.85 | P<0.01 |

statistically significant difference exists between the two groups under 96 h, but there was significant difference (p<0.01) over 96 h (Table 5).

VAP is defined as pneumonia in patients receiving mechanical ventilation and it is also a leading cause of sepsis with acute respiratory failure and a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in intensive care unit patients (Leroy et al., 2001; Tejerina et al., 2010). During 1992 to 2004, NNIS report reveals a median rate of VAP associated with mechanical ventilation to be 2.2 to 14.7 cases per 1000 patients per day in adult ICUs. The estimated mortality rate is between 20 and 70% (Cuellar et al., 2004).

VAP can be categorized into:

Early-onset VAP (EOP) occurs during the first 4 days of trachea cannula and artificial airway establishment and accounts for 50% of VAP, most often caused by phary- ngeal parasitic bacterium (such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus).

Late-onset VAP occurs at least 5 days after intubation and is most often caused by gram negative bacterium (for example, Enterobacter, Acinetobacter, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Badia and Torres, 2008; Niederman and Craven, 2005; Diaz et al., 2009; Medford et al., 2009).

There is a wide range of bacteria in the mouth, nose and pharynx , including various potential pathogenic bac- teria. The barriers of these areas plus lower respiratory tract of patients receiving mechanical ventilation are directly destroyed. Transient pressure decreased by air sac, change in posture or airway diameter cause the secretion to pass to the lower respiratory tract through the gap between endotracheal wall and catheter (Marra et

al., 2009).

Contemporary oral hygiene for ICU patients mainly uses normal saline or chlorhexidine mouth rinse to clean the oral cavity but they have no or short term disinfection effect. Antibiotic solution may increase the risk of resis- tance for pathogenic bacteria and is not recommended (D íaz et al., 2010). Many international scholars are exploring effective oral hygiene methods to reduce the incidence of VAP (Gastmeier and Geffers, 2007; Heyland et al., 2002; Keenan et al., 2002; Livingston, 2000). JUC Spray Dressing can provide the antimicrobial effect for 8 h and produces no drug resistance, providing an inno- vative solution to prevent the incidence of VAP.

The mechanism of JUC in reducing the incidence rate of VAP by killing and inhibiting pathogenic microorganism by electrostatic force. JUC spray has little irritation to mucous membrane and does not cause drug resistance after long term usage.

In this study, it was found that patients who had JUC spray applied to oral and nasal cavities had lower inci- dence rates of VAP, the proportion of early-onset VAP and bacterial colonization in trachea, mouth, nose and pharyngeal portion was compared to the control group. JUC is a safe and effective physical antimicrobial spray dressing for mouth, nose and pharyngeal cavity. Although there was no significant difference in the incidence of bacterial colonization in mouth, nose, pharyngeal cavity and trachea between the two groups of early-onset VAP (<96h), the colonization rate of early onset VAP (<96h) in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group.

JUC is a physical antimicrobial agent that can replace contemporary disinfectants for oral care and alleviate the setback of clinical drug resistance. It is a new method for preventing the incidence of VAP safely and effectively.

1930 Afr. J. Biotechnol.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank JUC-NMS Technologies Company Nanjing, China, for providing nanotechnology antimicro- bial spray (JUC) in this pilot clinical study. We also appreciate Miss Wei Li, the chief of critical care nursing group at ICU of Shenzhen People's Hospital for sacrifice in the observation of patients and data entry.

REFERENCES

Badia JR, Torres A (2008) . Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. In: Mechanical Ventilation (First Edition). P Peter J, Md, Fccm, L Burkhard, PhD , A Editorial. Philadelphia: W .B. Saunders, pp . 645-

649.

Bell RCCJ, Smith JD, Johanson WG (1983). Multiple organ system failure and infection in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Int . Med. 99: 293-298 .

Belusic-Gobic MCM, J uretic M, Cerovic R, Gobic D, Golubovic V (2007) . Risk factors for wound infection after oral cancer surgery. Oral O ncol . 43: 77-81.

Carolyn L, Cason TT , Sue Saunders (2007) . Nurses' Implementation of guidelines for ventilator-associated Pneumonia from the centers for disease control and prevention. 16: 28-37 .

Celis RTA, Gatell JM, Almela M, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Agusti-Vidal A (1988) . Nosocomial pneumonia. A multivariate analysis of risk and prognosis. C hest. 93: 318-324.

Charitos T , van der Gaag LC, Visscher S, Schurink KAM, Lucas PJF (2009) . A dynamic Bayesian network for diagnosing ventilator- associated pneumonia in ICU patients. Expert Syst. Applications , 36(2, Part 1) : 1249- 1258.

Chastre J, Fagon J (2002). Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Respir . Crit. Care Med . 165: 867-903 .

Chastre JTJ, Vuagnat A, Joly-Guillou ML , Clavier H, Dombret MC, Gibert C ( 1998) . Nosocomial pneumonia in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care, 157: 1165-

1172.

Chevret SHM, Carlet J, Langer M ( 1993) . Incidence and risk factors of pneumonia acquired in intensive care units. Results from a multicenter prospective study on 996 patients. European Cooperative Group on Nosocomial Pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 19: 256-264.

Cloke DJGJ, Khan AL , Hodgkinson PD (2004) . Mc Lean NR . Factors influencing the development of wound infection following free-flap reconstruction for intra-oral cancer. Br . J. Plast Surg. 57: 556-560 .

Costerton JWSP, Greenberg EP (1999). Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science, 284: 1318-1322.

Craven DE KL, Kilinsky V, Lichtenberg DA , Make BJ , McCabe WR

(1986) . Risk factors for pneumonia and fatality in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 133: 792- 796.

Craven DE, Steger K (1996). Nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adult patients: epidemiology and prevention in 1996 . Semin Respir . Infect . 1 1: 32-53.

Cross AS, Roup B ( 1981). Role of respiratory assistance devices in endemic nosocomial pneumonia. Am. J. Med. 70: 681-685 .

Cuellar Ponce de Leon L, Rosales R, Rosenthal VD (2004). Prospective Study To Evaluate Mechanical Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Rate in Intensive Care U nits in a Peruvian Public Hospital: Benchmark with NNIS American Rates. Am. J. Infect. Control, 32:

E114-E115.

D íaz LA, Llauradó M, Rello J, Restrepo MI (2010). Prevención no farmacológica de la neumonía asociada a ventilación mecánica. Archivos de Bronconeumología, 46: 188- 195.

Delclaux CRE, Blot F , Brochard L, Lemaire F, Brun-Buisson C (1997). Lower respiratory tract colonization and infection during severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: incidence and diagnosis. Am. J . Respir . Crit. Care Med . 156: 1092- 1098.

Diaz E, Ulldemolins M, Lisboa T , Rello J (2009) . Management of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Infect . Dis. Clin . North Am. 23:

521-533 .

Doré PRR, Grollier G, Rouffineau J, Lanquetot H, C harrière JM, Fauchère JL (1996). Incidence of anaerobes in ventilator-associated pneumonia with use of a protected specimen brush. Am. J. Respir . Crit. Care Med. 153: 1292-1298.

Elie A, Jean-Francois T, Muriel T (2006). Candida Colonization of the Respiratory Tract and Subsequent Pseudomonas Ventilator- Associated Pneumonia. C hest . 129: 110-117 .

Fagon JYCJ, Domart Y, Trouillet JL, Pierre J, Darne C, Gibert C ( 1989). Nosocomial pneumonia in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Prospective analysis of 52 episodes with use of a protected specimen brush and quantitative culture techniques. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 139: 877-884.

Gastmeier P, Geffers C (2007) . Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: analysis of studies published since 2004 . J. Hospital Infect. 67: 1-8.

Gosney MAPA, Corkhill J, Millns B, Martin MV (1999). Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicaemia from an oral source. Br . Dent. J. 187: 639-

640.

Haley RWHT , Culver DH , Stanley RC, Emori TG, Hardison CD, Quade D, Shachtman RH, Schaberg DR, Shah BV ( 1981). Nosocomial infections in US hospitals, 1975- 1976: estimated frequency by selected characteristics of patients. Am. J. Med . 70: 947-959.

Qinhua He, lixian He (2004) . Progress of Study in Preventing Ventilator- Associated Pneumonia. Foreign Medicine, Fascicule of Respiratory System. 6: 122- 124.

Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Dodek PM (2002). Prevention of ventilator- associated pneumonia: Current practice in Canadian intensive care units. J. Crit. Care, 17: 161-167.

Keenan SP, Heyland DK, Jacka MJ, Cook D, Dodek P (2002). Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Crit. Care Clin . 18: 107- 125.

Langer M MP, Cigada M, Mandelli M ( 1989). Long-term respiratory support and risk of pneumonia in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Unit Group of Infection Control. Am. Rev. Respir . Dis. 140: 302-305.

Leroy O, Sanders V, Girardie P, Devos P, Yazdanpanah Y, Georges H

(2001) . Mortality due to ventilator-associated pneumonia: Impact of medical versus surgical ICU admittance status. J. Crit. Care, 16: 90- 97.

Livingston DH (2000). Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Surg. 179(Sup 1): 12- 17 .

Markowicz PWM, Djedaini K, Cohen Y, C hastre J, Delclaux C, Merrer J, Herman B , Veber B, Fontaine A (2000). Multicenter prospective study of ventilator-associated pneumonia during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am. J. Respir. Crit . Care Med . 161: 1942- 1948 .

Marra AR, Cal RGR , Silva CV , Caserta RA, Paes ÂT , Moura Jr DF (2009) . Successful prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in an intensive care setting . Am. J. Infect. Control, 37: 619-625.

Medford ARL , Husain SA, Turki HM, Millar AB (2009). Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J. Crit. Care, 24: 473.e471- 473.e476.

Munro CL , Grap MJ, Jones DJ, McClish DK, Sessler CN (2009). Chlorhexidine, toothbrushing, and preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adults. Am. J. Crit. Care, 18: 428-437.

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance ( NNIS) System ( 1999). National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System report , data summary from January 1990- May 1999. Am. J. Infect. Control , 27: 520-532.

Niederman MS , Craven DEC (2005) . Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired, Ventilator-associated, and Healthcare- associated Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171: 388-416.

Prevention Cf DCa (2000) . Monitoring hospital- acquired infections to promote patient safety: United States, 1990- 1999. MMWR. 49: 149-

153.

Rello JAV, Ricart M, Castella J, Prats G (1993) . Impact of previous antimicrobial therapy on the etiology and outcome of ventilator- associated pneumonia. C hest. 104: 1230- 1235.

Rello JRM, Jubert P , Muses G, Sonora R , Valles J , N iederman MS

(1997) . Survival in patients with nosocomial pneumonia: impact of the severity of illness and the etiologic agent. Crit. Care Med. 25: 1862- 1867.

Li et al. 1931

Salam MASH, Nomura Y, Matin K, Miyazaki H, Hanada NM (2001) .Isolation of opportunistic pathogens in dental plaque, saliva and tonsil samples from elderly. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 54: 193- 195.

Senpuku H SA, Inoshita E, Tsuha Y, Miyazaki H, Hanada N (2003). Systemic disease in association with microbial species in oral biofilm from elderly requiring care. Gerontology, 49: 301-309.

Senpuku H TA, Takada M, Sato Y, Hanada N (2002). Reproducibility of oral bacterial isolation in the elderly. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 33: 61-62.

Senpuku H TA, Uehara S , Kariyama R, Kumon H (2006) . Postoperative infection by pathogenic micro-organisms in the oral cavity of patients with prostatic carcinoma. J. Int. Med. Res . 34: 95-102 .

Tada AHN, Tanzawa H (2002). The relation between tube feeding and pseudomonas aeruginosa detection in the oral cavity. J. Gerontol . Biol. Sci . Med. Sci. 57: M71-72.

Tada A WT , Yokoe H, Hanada N, Tanzawa H (2002). Oral bacteria influenced by the functions status of the elderly people and type and quality of facilities for the bedridden . J. Appl. Microbiol. 93: 487-491.

Tejerina E, Esteban A , Fernández-Segoviano P, Frutos-Vivar F, Aramburu J, Ballesteros D (2010). Accuracy of clinical definitions of ventilator-associated pneumonia: Comparison with autopsy findings .

J. Crit. Care, 25: 62-68.

Torres AAR, Gatell JM, Jimenez P, Gonzalez J, Ferrer A, Celis R, Rodriguez-Roisin R (1990) . Incidence, risk, and prognosis factors of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Am. Rev. Respir . Dis. 142: 523-528.

U.S. Department Of Health And Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control (1997). Guidelines for Prevention of Nosocomial Pneumonia. 46: RR- 1.

Vincent JLBD, Suter PM, Bruining HA , W hite J, Nicolas-C hanoin MH, W olff M, Spencer RC, Hemmer M ( 1995) . The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) Study. JAMA. 274: 639-644.

Zeng Y, Deng R, Barry HS, Yeung W , Loo TY, Mary Cheung NB, C hen JP, Bingrong Z , Yifu F, Lanzhu H, Mingxing L, Min W (2008) Application of an antibacterial dressing spray in the prevention of post-operative infection in oral cancer patients: A phase 1 clinical trial. Af

© 2020 南京神奇科技开发有限公司 版权所有 洁悠神学术中心